Replica exchange nested sampling

To get the most out of this section, you should already be familiar with the basics of nested sampling (NS). If not, feel free to check out this gentle introduction first.

The shortcomings of MCMC

We’ve seen that to generate independent samples from the constrained regions at each NS iteration, Markov-chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) random walks are typically employed. While MCMC is essentially the only viable method for sampling in high-dimensional systems, it also comes with serious limitations.

To illustrate this, consider the bimodal energy surface shown in the visualization below. This surface has been deliberately constructed with a broad, shallow high-energy basin and a significantly narrower, deeper global minimum. Such a structure poses a challenge for NS, which operates top-down by evolving walkers from higher to lower energy regions. For the process to succeed, MCMC chains must "find the entry" to the global minimum at the right moment.

Click through the visualization to see how this may fail in practice.

While exploring the visualization, pay attention to the following:

- Entry closing: at iteration 9 the entry to the global minimum mode is about to close.

- Barrier formation: From iteration 10 onward, an infinitely high barrier forms between the metastable and global minimum basins.

Once this barrier has formed, it becomes exceedingly unlikely for MCMC to re-enter the global minimum. A successful transition would require a large, well-directed step—something increasingly improbable as the barrier widens.

While the example surface may seem overly idealized, similar situations are common in materials simulations. First-order phase transitions—such as the shift from a liquid to a crystalline phase—often involve dramatic reductions in accessible phase space. In this analogy, the liquid phase corresponds to the broad, high-energy basin, while the crystalline phase represents the narrow, low-energy well.

RENS – Cooperative NS Simulations

What if we could run several NS simulations in parallel and allow them to cooperate?

Replica exchange (RE) provides a statistical framework for exchanging samples between different distributions, while rigorously preserving the statistics of each one. Since the walkers at NS iteration

To introduce the idea of replica-exchange nested sampling (RENS), let’s return to the bimodal energy surface. While not the most sophisticated use case, it’s illustrative. Suppose we run two NS simulations in parallel. The standard NS procedure continues in each, but we now periodically perform RE swap moves. The swap rule at iteration

Single RE swap:

- pick a random walker

from simulation - pick a random walker

from simulation - swap if

inside and inside

This mechanism is best understood by walking through a concrete example. The visualization below shows both simulations (we call them replica

Clicking through the simulation you should see the following:

- In simulation

, the global minimum basin becomes disconnected at iteration 14. - From then on, the global minimum is no longer sampled—an independent NS run would be stuck.

- Simulation

successfully enters the global minimum basin at iteration 11. - At iteration 19, a walker from

residing in the global minimum is swapped into —repopulating the previously lost region. - Initially, most swaps are accepted, but the acceptance rate gradually decreases.

Introducing a new toy model

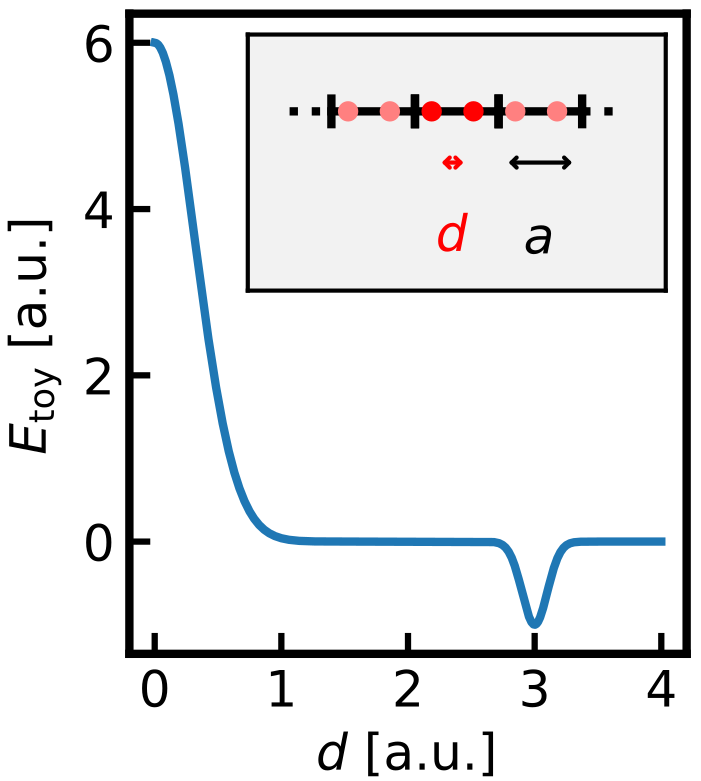

The previous example used a simple 2D bimodal energy surface. Let’s now introduce a toy model that’s a bit closer to real-world materials simulations. We consider a periodic chain of particles interacting via the pair potential shown below:

js Copy Edit

We represent the system as two particles in a periodically repeated box. Due to translational invariance, we can fix one particle at zero and move only the second one. This gives us two degrees of freedom:

- The lattice parameter

(box size), - The position of the second particle

(interparticle distance).

The visualization below shows the 2D configuration space, along with the unit cell and its two particles. You can interact with

Pressure RENS

This setup lets us apply RENS in a much more compelling scenario: simulations with different energy landscapes. Recall that the acceptance probability of RE swaps depends critically on the overlap between the involved distributions. If the distributions differ too much, swaps will rarely be accepted. This is where materials science offers a natural use case: an external pressure introduces a continuous deformation of the energy (more precisely, enthalpy) landscape. Because we often want to compute NS partition functions across a range of pressures anyway, this structure is a perfect match for RENS. Below you can explore a simple example using two replicas—one at lower pressure (left), one at higher pressure (right).

Observe how pressure subtly reshapes the likelihood-constrained distributions. It’s precisely this controlled diversity across simulations that gives RENS its true strength. Unlike the simplified two-replica examples shown here, RENS is typically applied with many replicas—often around 10—each exploring slightly different conditions. Think of it like a team of skilled football players, each with their own specialty, working together to cover the entire field more effectively than any individual could alone.

If this sparked your interest, feel free to explore our paper, where we apply RENS to more complex atomistic systems—including realistic simulations of silicon:

Unglert, N.; Pártay, L. B.; Madsen, G. K. H. Replica Exchange Nested Sampling. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jctc.5c00588.